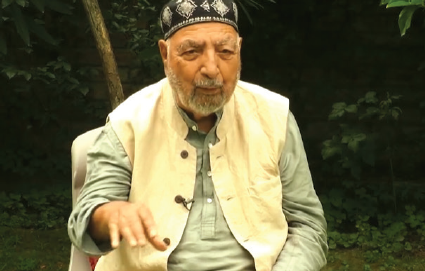

With an impeccable lineage and an enviable legacy, Mir Mohammed Farooq Nazki, was a man of many parts: professionally a broadcaster and a bureaucrat, intellectually a poet and literary critic, personally an engaging conversationalist and raconteur and socially an enlightened intellectual and influencer. The whole, however, was more than the sum of parts.

He was the archetype of a generation which inherited the traditions of the old order and imbibed the values of the new one. His generation, which he exemplified, was torn in the transition: committed to the new but contained by the old. It was a battle he fought all his life at different levels. The older generation saw him as carrying forward their legacy and the younger generation saw him as the harbinger of their aspirations. He lived his present as a mentee of the past and a mentor for the future. It was indeed a tall order but an exciting and fulfilling life.

He was the only one I knew who was totally at ease starting a day participating in a Khatme sharif with devotees at a venerated shrine, hold an intense conversation in the afternoon with colleagues at the India Coffee House equating monotheism with the Absolute in the Trika and then at night drown his sorrows with comrades at the fabled Lab Kouls.

He was anything but unidimensional and insipid. His life had colour. It had character. There was idealism and romance. Above all, liberalism, tolerance, and inclusivity. Farooq Nazki was, in that sense, the last of the Mohicans. With him a bit of the uniqueness that is Kashmir has gone. And that is the real loss.

His being was shaped by two distinguished individuals; first and foremost, his father, Mir Ghulam Rasul Nazki, a larger-than-life patriarch, who he was in awe of. Second, his father-in-law, Syed Mubarak Shah Gilani, “Fitrat”, whom he admired. He for ever rebelled against his father only to seek his attention and approval. More for his persona than for his poetry. And in this, he drew upon the life of Fitrat sahib; a free-spirited practising Sufi who used Kashmiri cultural practices to navigate religious ritualistic norms and enlarged the boundaries of the socially acceptable behaviour. Farooq Nazki found an ideal, and timely, alibi in him; his father’s well-regarded friend, to rationalise his own unconventional behavioural instincts and actions.

Born in feudal Kashmir in a quaint village, Madar, in Bandipora, he grew in the valley during the transformational decades of the 1950s and 60s when intellectuals of various hues — writers, poets, artists — descended on Kashmir. Many of these were his father’s friends and colleagues, so he grew up looking up to, and occasionally rubbing shoulders with, doyens of Urdu poetry like Josh Malihabadi and intellectuals like Khawaja Ghulam Syedain, whose sartorial elegance he was to emulate later in life, including occasionally wearing a watch on the right hand!

He observed the transition from monarchy to democracy not so much as a political transformation or economic realignment but as a cultural upheaval through the private interactions and radio programs of his father who was working for the Radio Kashmir. All this was the scaffolding for the creative edifice he was to build.

The big structural break, which opened new intellectual vistas for him, and honed his broadcasting skills, was his stint in Europe, in particular Germany. He was fortunate to be there in the mid-seventies when the experimental phase for German Television was at its peak. He absorbed the new aesthetic vision and the possibilities that emerged with the introduction of technologies like magnetic recordings and techniques like chroma keying. He used all this in Srinagar Doordarshan which, incidentally, was started in 1972, the third TV station in India after Mumbai and Delhi.

After having interacted with legends like Peter Utsinov, he returned a transformed man. He came back to see Kashmir as a conservative order: elitist, patriarchal, moralistic and, crucially, statist in its cultural moorings. He saw himself as a harbinger of change and came into his own as a broadcaster. He propagated popular culture and introduced Boney M, the band which mixed soul, funk, pop, and hip hop making him “Daddy Cool” for his daughter, Roohi.

He mentored and influenced artists, producers, writers, composers and directors in dealing with the new mass medium of television and build a new visual language and narrative. This, along with his strong foundations in native cultural expression, created a heady brew.

Growing up in Kashmir, one would often hear people humming on the streets his very popular background lyrics – Dal Chaen Malrain Seemab Deeshith, Aaftab Woshlaan Woshlaan Drav — for the hugely popular TV serial Gul, Gulshan Gulfam depicting the livelihood impairment due to the onset of militancy in the valley.

Thus began the final phase of his career which saw him use his considerable expertise and experience to devise the communication strategy to counter the separatist narrative and the pro-Pakistan propaganda. Overtime, he got closely associated with the deep state and was widely seen as the last man standing for India in those turbulent times of 90s in the valley.

Even as he was loyal in his professional duties, the poet’s heart bled to write heavily layered poems movingly describing the plight of his people. His poem on mothers destined to wash the blood-soaked garments of their children made individual mourning collective grief, in the process converting “yarbal”, a community platform of fun and banter to a one of shared suffering.

He could never reconcile with the schism that militancy created between the Pandits and Muslims. His association with Kashmiri pandits was deep, intensive to the point of being ideological. Not only was he aware of the richness of Trika shastra as a philosophic doctrine that originated from Kashmir, he was also very emotionally attached with the community often remembering that he was an 8th generation descendant of Dattataree Ganesh Koul from his maternal side.

Dedicating his award-winning book of poems, Lafz Lafz Noha, to his childhood friend and colleague Somnath Sadhu, he owns up to the tragedy that befell Kashmir. The Ek Intesaab Aur is evocatively beautiful that has the more potential to reunite the two communities than any Truth and Reconciliation Commission can have.

Somnath Sadhu, teray naam

Jaanta hai tumhari maa

Kamli

Kashmir choad kar gaye hai

Aur apnay saath chandi kee who thali be lay gayee hai

jis main woh

hum dono kay liya khana paroste thee

Kya tu jaanta hai ki

Woh meray darr say Kashmir say baag gayee hai

Tumahra

Farooq

It became difficult to see a consistent world view in his works as he led a schizophrenic existence in the violent decade of 1990s that mauled his personality. He and his family suffered a lot, socially, during the start of militancy as he was seen as a collaborator.

My personal relationship started with him during this period. Ostensibly enjoying the trappings of power he was, like any Kashmiri, in deep distress and anguish searching for answers that were not readily forthcoming. He had delved back into Ibn Arabi and I was an unintended beneficiary as I got introduced to the enriching world of Shaykh al-Akbar Muhyiddin Ibn al-Arabi, the spiritual offspring of Ghaus-e-Azam Shaykh Abdul Qadir al-Jilani. It is a debt I can never repay.

Fresh from academic works, I referred him to the Edward Said’s work on Orientalism. I vividly remember in the winter of 1996, when he was staying over at our modest one BHK apartment in New Delhi, he was virtually in a trance. He called over his best friend Mohmmed Amin Andrabi and deep dived into Said. He was erudite enough to pick up the influence of Martin Heidegger, the German philosopher whose works he had got acquainted with during his stay in Germany. And went onto decipher the networks of social power delineated by Michel Foucault.

This intellectual pit-spot notwithstanding, he was back to basics. A few years later, he once read out to me a poem of his, the only time he did so, an ode, on the Ascension of the Prophet Muhammad (SAW) on the night of Meraj. It is symbolic that he started his next journey on the Shab-e-Meraj when the entire vicinity of his resting place at Malkha was reverberating with invocations. He had shown the 300-verse poem to Rehman Rahi sahib, whom he considered to be the greatest litterateur of modern Kashmir, only to be told that it was his finest contribution to Kashmiri poetry. He had a heretical streak in him, some of which is at play in Meraj nama.

There was a little-known risqué side to him. He is the only one I know who remembered Makhan Lal Mahav ribald poem in full and was a repository of the fabled explicit and rather crude Hajini sahib jokes! No wonder he loved the poetic idiom and expression of Akhtar-ul-Iman, a favourite poet of his along with Miraji, on whom he had written a thesis.

While composing poetry was undoubtedly a creative process engendered by the desire to express himself, it seemed to me that it was also a pure skill for him. No wonder then he was so good in translating. His translation of Hasrat Mohani’s delicate poem, Chupke Chupke Raat Din Aasoo Bahana, immortalised by Ghulam Ali was masterly. Choori chaepi doh raat cheshmav khoon haarun yaad chum not only retained the poetic sensibility and the lyrical structure of the poem but also made it culture-specific to Kashmir.

The pure skill of the craft of composing was also in evidence as an exponent of the Abjadi system of tareekh-e-wafaat wherein embedded in words are numbers that reveal the date of death. His own tareekh-e wafat has been composed by his younger brother Ayaz Rasool Nazki, an accomplished poet, as follows:

Char din ki Zindagi main koi yan kamil huwa,

Nama-e-Meraj gar amaal main shamil huwa;

Shayiray sheerin bayan phir dar iram vasil huwa,

Sal-e-wasle Nazki Farooq be hasil huwa

His own couplet, in Manto style, best serves as his epitaph:

Naav Farooqun wuchith peeris lekhith, sorui mashum,

Naav panui paen panas yaad pavum yaad chum

Notwithstanding any of his many facets, the loud sotto voce, in the three days of mourning following his death, there was one thing that resonated with him as a friend, a dost. He took his birth on Valentine Day a tad too seriously, much before it became a commercial fad. His love and affection were not restricted to his family or friends alone. Cutting across age, gender, class, religion, and region, he built a network of relationships based on his defining trait of being charming and non-judgemental.

Tail piece:

His wit and repartee skills were legendary. While he was Media Advisor to Chief Minister Farooq Abdullah, I wrote a rather harsh piece in Greater Kashmir on Omar Abdullah being the National Conference candidate in the parliamentary election of 1998. On reading it Farooq Abdullah got furious and strode into his Media Advisor’s room in the secretariat waving the newspaper in his face demanding to know how he let his son-in-law write against him. Unfazed, Nazki sahib replied, “If the tallest of all Kashmiris, Sheikh sahib, could not control his son-in-law, who am I to be able to do that!” Farooq Abdullah was not only disarmed but quite charmed.