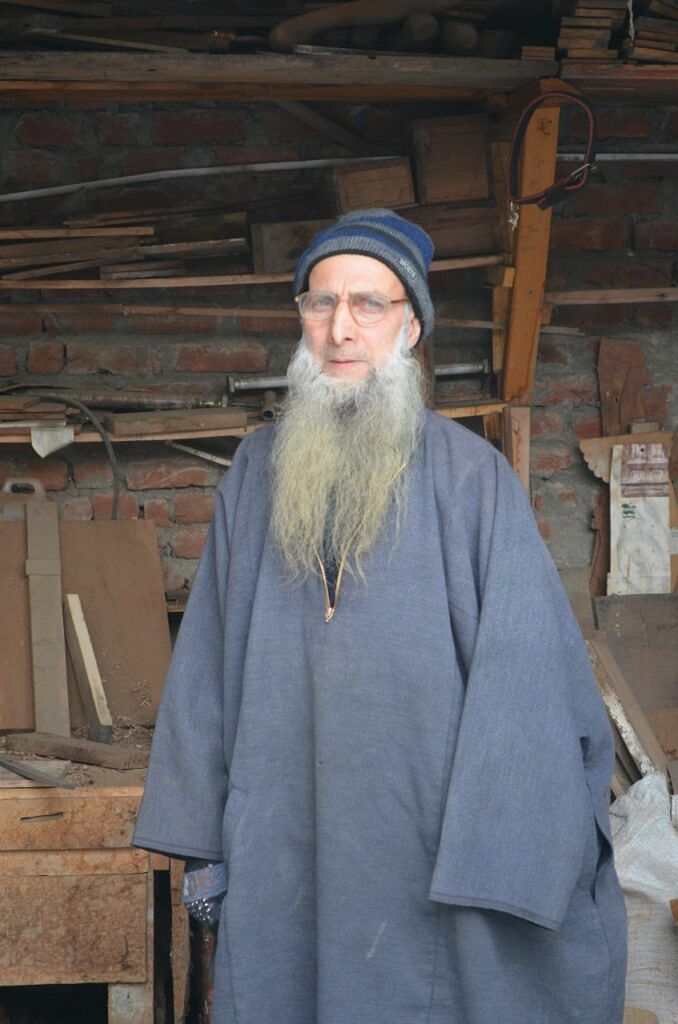

Unlettered, as most of his generation was, Ghulam Nabi Dar, a 68-year-old man from Malik Sahib area of downtown Srinagar, did not own a pen and paper.

Poor Dar was in fact discharged by the school authorities when he was in 3rd standard, for his family was unable to purchase a uniform for him and pay his school fees.

Yet, in the parallel world, Dar turns out to be a prodigy, who picked up the metaphorical wood carver’s chisel to create magic on raw planks of wood on one hand and carve a niche for himself in the art of woodcarving on the other. Does not matter he could not be a student, sexagenarian Dar has been a master anyway!

Born in a poor family, the “enforced” school dropout, being the eldest to his parents, had the added responsibility on his shoulders due to which he had to look for work at once.

The challenge was further exacerbated given his father’s business losses around the same time. “I had no footwear and used to cross the Safakadal bridge bare-feet,” Dar vividly recalls.

Soon, he started to work under one Abdul Razzaq Wangnoo, a local wood carving artist and being a newbie, Dar’s work was to do dishes and carry the wood carving tools for Razzaq, he told Greater Kashmir.

Dar worked with Wangnoo for five years and it was only in the last year, the master started to pay him two rupees fifty paise a day as monthly salary. “The first four years, he only paid me on Eid and whenever he liked to,” Dar said.

But more than the monetary returns, it was the passion for learning the art, which kept him going.

After leaving Wangnoo’s workshop, Dar came under the aegis of another wood carving artist in the neighborhood, Abdul Aziz Bhat and used to carve designs on windows and doors at a renowned firm namely ‘Subla & Company’.

The shift to the new master was the turning point in Dar’s career as he developed a fascination for the art even as his family also supported him seeing their son’s knack for the art of woodcarving.

“My father wanted me to learn this art perfectly, so he asked Aziz even if he wanted to pay me less, he could, but told him to teach me effectively,” Dar recalled.

Seeing his parents’ eagerness to see their son as an artist, Dar too developed a passion. He said he fell in love with the art “like Majnu fell for Laila”.

Dar recalled how he used to borrow paper to sketch designs of flowers in order to replicate them on the wooden planks and articles for which people called him a ”mad man”.

“But I loved what I used to do and their comments didn’t bother me,” Dar said.

While working with Aziz, Dar also sneaked into the store room once where expensive and unique masterpieces were kept and would marvel at the pieces of art for some inspiration.

“One fine day when I was jubilantly drawing designs, the manager came and saw me. He was furious at first, but upon learning about my love for the art, he permitted me to sit in the room daily for four hours,” recalled Dar with a giggle.

The sexagenarian said that he never settles for a single design and tries to carve different designs every time he makes a new piece.

“I want my hands to represent and design something unique and for that, I keep imagining things around,” he said.

A wall hanging portraying the Dal Lake, the shrine of Makhdoom Sahib (RA) and the Hari Parbat fort nearby to count a few designs.

Apart from his knack for impromptu designs every single time, his dedication and professionalism wherein he pays attention to the intricate details on a particular piece of art are awe-inspiring.

Dar reminisced about a particular wall hanging he made in 1974 taking as many as six months to complete it!

While he loved to deliver pieces of art that were unique and sophisticated, Dar needed to feed his family as well, “so I worked on routine items to earn a few more bucks,” he said.

On another occasion, Dar would design a wall hanging of a ‘Kashmiri Panchayat’ depicting a Muslim, Sikh, Hindu and Christian members sitting at a panchayat in a Kashmiri village.

“I loved it because it portrayed the reality of religious harmony in Kashmir and also our culture,” he said.

Impressed by his art, a renowned company awarded him Rs 500 for the wall hanging and put it in their own showroom.

“In those days, Rs 500 was more than enough prize money, but what satisfied me more was my work being recognized and appreciated,” Dar remarked.

In 1995, Dar was further motivated to excel in the field of art when he received a national award for his impromptu wooden box.

“I was shocked as I was declared the winner within a year only because the results were usually declared after a gap of six years. I was a bit lucky,” Dar said, adding: “This motivated me to design more and more products and kept me going.”

More than any government award, Dar recalled an episode wherein he got to know the acknowledgement for his art form from a man from the Middle East.

In 1979, Dar happened to meet a doctor from Baghdad, the Iraq capital who was on a vacation in Delhi. The doctor was so impressed with Dar’s work that he invited him to the Iraqi capital and arranged all the necessary travel related documents all by himself, Dar recalled.

“As I’m unlettered, I couldn’t speak their language but I worked there for twenty two months and during that period, I learned a bit of Arabic and a little Persian too,” he said.

Besides Iraq, Dar has also travelled to countries including Germany and Thailand because of his zest to learn and excel in his art.

Dar, who has married off his three daughters and a son, would earn a minimum of Rs 4, 000 a day during his heydays.

He however lamented that the artists in Kashmir were struggling as on date saying he feared that with the death of few remaining artists, “the art, which represented Kashmir, will die too”.

The only consolation Dar has is that he has perhaps been able to pass on the art to his only son, Abid Ahmad, 32, who is equally (and luckily) eager to embrace the art and imparts training in the skill at a local Industrial Training Institute.

“People in Kashmir don’t value artists even though they pay a huge amount of money when buying our products. People look down upon artists and consider our work as ‘low profile’, but I wanted to break this stereotype,” Ahmad said.