About a year ago, I wrote an article on majoritarianism inSouth Asia, which is feared as much as monarchism. Several well-meaningpeople—academics, writers, intellectuals, and opinion makers—are worried,rightly so, about the overwhelming victory of the BJP in the recent generalelections in India. But wouldn’t it behoove those opinion makers andintellectuals, some of whom are my friends, to hold the Indian NationalCongress (INC) just as accountable for having, historically, given short shriftto constitutional checks and balances, particularly in terms of center-staterelations?

We need more nuanced readings of national politics if we areinvested in invigorating the very well written Constitution of India with thedignity and vigour that it deserves.

Since Independence in 1947, the Indian polity has undergonedislocation and restructuring, with, as Aijaz Ahmad tells us, “contradictorytendencies towards greater integrative pressures of the market and thenation-state on the one hand, greater differentiation and fragmentation ofcommunities and socioeconomic positions on the other” (191).

The unitary concept of nationalism that politicalorganizations like the Congress and the BJP have subscribed to challenge thebasic principle that the nation was founded on: democracy. In this nationalistproject, one of the forms that the nullification of past and present historiestakes is the subjection of ethnic and religious minorities to a centralized andauthoritarian state. The unequivocal aim of the supporters of the integrationof J & K into the Indian union, which included honchos of the IndianNational Congress (INC) was to expunge the political autonomy endowed on theState by India’s constitutional provisions. According to the unitary discourseof sovereignty disseminated by nationalists of the INC, J&K wasn’t entitledto the signifiers of statehood.

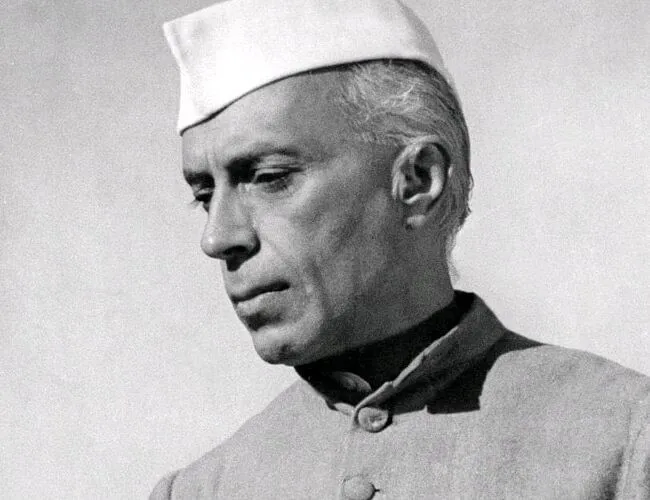

The INC proclaimed the victory of integration in J&K,which had sought the subsumption of ethnic and religious minorities into acentralized and authoritarian state since the 1940s. The furtherance of thiscentrist movement was enabled by the complicity of one of the architects ofdemocracy and secularism, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. His adherence to theunitary discourse of nationalism galvanized the suppression of demands for theautonomy of J & K state. These integrative and centralist measures were metwith massive opposition, which the INC suppressed at the time.

The financial and fiscal integration of the state into theIndian Union; the authority given to the Indian Supreme Court to be theundisputed arbiter in J&K; the application of the fundamental rights thatthe Indian constitution guaranteed to its citizens to the populace of J&Kas well, but with a stipulation: those civil liberties were discretionary andcould be revoked in the interest of national security. These measures wereimplemented in J&K by the INC government at the Center.

Jagmohan, the governor imposed by New Delhi on the people ofJ & K, was adept at carrying out the oppressive policies of his patrons toa tee. Formerly Vice Chairperson of Delhi Development Authority, he had beenhand-in-glove with Sanjay Gandhi, son of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, incarrying out the demolition of Turkman Gate slums and forced sterilizations—measuresthat adversely impacted the Muslim community. Governor Jagmohan employedbelligerent measures to pulverize the support that some religio-politicalgroups had managed to garner in the Valley: night-long house-to-house raidsbecame the order of the day. Governor Jagmohan’s autocratic rule and thetyranny of mercenaries resulted in the militarization of Kashmiri culture andthe torture of hapless Kashmiri civilians. Strategies deployed by successiveCongress regimes had the adverse effect of stunting the development ofdemocratic and civic structures conducive to suffrage and participatoryprocedure in J & K. The conscious policy of the INC to erode autonomy,populist measures and democratic institutions in J & K further alienatedthe people of the state from the Indian Union.

In the 1970s and the 1980s, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’sCongress regime characterized every demand for regional empowerment in Jammuand Kashmir as potentially insurgent, and discouraged the growth of aprogressive generation of Kashmiris.

More recently, the Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) SpecialPowers Act was enacted in 1990 by the Union government in New Delhi and itsrepresentative in the state, the Governor, the authority to arbitrarily declareparts of J&K “disturbed area” in which the military could be willfullydeployed. At the time, the Congress was a major player in the federalgovernment. The introduction of other severe laws by the Government of Indiahas made it further non-obligatory to provide for any measure of accountabilityin the military and political proceedings in the state.

The INC should be held just as accountable for having failedto truly revive the spirit of parliamentary democracy.

As I’ve said before, national parties will need toreconceptualize their politics in order to pay attention to the emergence ofpeace, political liberty, socioeconomic reconstruction, and egalitariandemocratization, good governance, and resuscitating democratic institutions.