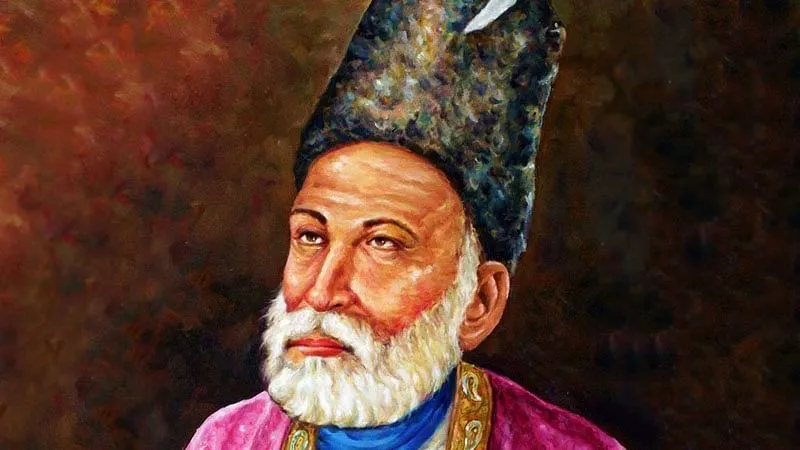

Ghalib, no doubt, is the most famous poet of Urdu, fit to rank with the greatest poets of the world. A master of the condensed style, Ghalib is the most quotable poet of Urdu, some of whose couplets may rightly be called the capsules of condensed wisdom and wit. The world knows him as a legendary poet, diehard romantic and philosopher. No doubt, he was all these and much more, but above all, he was a great humanist. Unfortunately, this aspect of his personality has not received as much attention as it deserved. When we recall some of his well-known verses and we have a peep into his heart, the light of humanism and humanity very much shines there.

My father had introduced me to Iqbal in my early teens by presenting me Bange Dara, whose poems titled “Himalaya” and “Dua” had touched my inner chord even at that tender age and had learnt these by heart. But as I grew, I developed a huge admiration for Ghalib, an essay on whom won me a first prize in an essay competition in the college. Even though I took up law in post graduation, I always kept a Dewan by my side, just in case I had a mood swing, I would solace in one or the other verse in it. It was a panacea for all moods and had an answer for almost all existential questions. The realization that Ghalib was basically a remarkable humanist dawned on me in later years, by which time I had made it a practice to gift a Dewan to my friends.

The fact that Ghalib was a genious par excellence is not lost on any of us. Having started writing mature poetry in Urdu at the tender age of eleven, which he gave up to write in Persian for over a decade and produced stuff five times more, he returned to write beautiful Urdu poetry which was as refreshing, if not more, as his teenage poems and which won him world recognition that not many of his ilk had the luck to enjoy. There is only one explanation for this in Sanatana tradition and that is that Ghalib was carrying his genius from his past births.

Ghalib’s humanism was truly secular, comprehensive and touching every aspect of life including its values, meaning, and identity. It was not at all atheism, which concerns only the nonexistence of god, but much broader because he understood clearly that there was lot more to life, which only secular humanism could address. His humanism was nonreligious, espousing no belief in a realm or beings imagined to transcend ordinary experience. His humanism incorporated the enlightenment principle of individualism, which celebrates emancipating the individual from traditional controls by family, church, and state, increasingly empowering each one of us to set the terms of our own life. Ghalib’s secular humanism was naturalistic, even though he did not directly proclaim so. While not denying the existence of God, he knew that knowledge gained without appeal to reason and the natural world was unreliable.

Ghalib, the poet, makes a fine distinction between aadmi and insaan. According to him, a person devoid of human compassion exists just as a living creature. It is man’s sensitivity to his fellow beings that makes him a complete human being. Ghalib’s poetry is replete with instances of his deep concern for others. Writes Dr Ibadad Bareilwy, a respected Urdu litterateur: “Ghalib’s greatness lies in his ability to empathise with the pain and suffering of others. It would not be an exaggeration to say that insaniyat or humanism forms the essence of Ghalib’s life and works.” Ghalib was deeply aware of the vagaries of life. His acceptance of human vulnerability and his desire to stand by people in their hour of need is what makes him special.

Though a Muslim by birth, we find Ghalib emphasizing on the importance of universal brotherhood, love and affection with other human beings irrespective of colour, creed, race or religion. Ghalib would also lay emphasis on the importance of moral education in his poetry. A true democrat at heart, the study of his letters reveals that he had adopted the mode of correspondence to guide his numerous disciples whose poetic works were used to be moderated and corrected by him. We also find that Ghalib had a very close and intimate relationship with his disciples inasmuch as they felt free to share their thoughts or for that matter, anything with him, even if it was through letters.

Ghalib’s poetry and prose are distinguished for his sparkling wit, tough ratiocination and his innovations in technique and diction. He was a gifted letter writer too. His letters gave foundation to easy and popular Urdu. Earlier, letter writing in Urdu was highly ornamental. He made his letters “talk” by using words and sentences as if he were conversing with the reader. According to him Sau kos se ba-zaban-e-qalam baatein Kiya Karo Aur hijra mein visaal ke maze Liya Karo (from a hundred of miles talk with the tongue of the pen and enjoy the joy of meeting even when you are separated and far away). His letters to close friends were very informal even as he would write very formally to strangers and authorities. In one letter he wrote, “Main koshish karta hoon ke koi aisi baat likhoon, jo padhe khush ho jaaye” (I want to write lines which would make the reader feel happy.)

In his poetry Ghalib talks about human emotions i.e. emotion of love, amusement, desire and longing, hatred, jealousy, despair, disappointment and conflict in man, etc. He uniquely believed that the emotion of hatred is even stronger than love. Sometimes we can not tolerate even our favorite person mentioning the one whom we hate badly. If a favourite person talks even in derogatory sense about the one whom we hate, we start disliking the favourite person also. Sample this: Zikr mera ba bad i bhi use manzoor nahin, Ghair ki baat bigar jaae to kuch door nahin. (She (the beloved) does not want to hear me mentioned even in a derogatory way. If the other’s (the rival’s) matter gets spoiled, I would not be surprised.) Ghalib had full consideration of the positive aspects of hatred, malice, enmity and hostility. This has been his basic perception. According to him, hatred and enmity are infact the symbol of friendship and closeness. We can not feel hatred and enmity from a stranger or unknown person. These emotions get harbored about a person who has been close to us because hatred and enmity express a deep relationship between two persons.

The virtue of forgiveness in Ghalib had floored me when I had read this verse of his: Na suno gar bura kahe koyee/ Na kaho gar bura kare koyee/ Rok lo gar galat chale koyee/ Baksh do gar khata kare koyee (Don’t heed bad words/ don’t speak of the misdeeds of others/ if one is on the wrong path, stop him/ forgive those who err.) I would instantly recall the poem titled “The Three Rules” I had read in my English text in my seventh standard horted us to return good for evil. The sonnet was also reminiscent of Gandhi’s three monkeys and seemed to have been carved in the Hindu tradition of kshama being the ornament of the brave. Being generous even in forgiveness was the rare attribute that Ghalib had been bestowed with. Sample this: Diya hai dil agar usko / Bashar hai kya kahhiye/ Hua raqeeb namabar hai, kya kahiye (What can one say if he, too, has fallen in love with her and becomes my rival? After all, he is human too, and has a heart.)

Ghalib placed a greater emphasis on seeking God rather than ritualistic religious practices. The emotional lay of Ghalib’s poetry in the perspective of the Buddhist discourse can be explained in the contours of Shooniyata (the Great Emptiness) which is neither a religious or a metaphysical concept, nor is it a way of meditation. It is a way of thinking that strikes at the root of every concept, ideology, belief, and social practice. It enables one to go beyond the apparent to see the otherness of it and it is what that runs through Ghalib’s entire poetry. Yet, unlike the Buddhists, salvation is not something Ghalib longed for; he strived for highlighting the sufferance of people. Time and again, Ghalib through his unmatched wit, makes defiant gesture against insensitivity, powers that be and of course, money. For him, even poetry is an act of subversion.

Ghalib had a great intuition. He could peep into the future. That’s why he remained calm and poised even as he led a life bordering on miseries. He seemed to be acutely aware of the impending change in the world polity sponsored by the Europeans. On one occasion, he even chided Sir Syed, who had approached him to write a foreword to his book written in praise of Ai’n-e Akbari. Sir Syed might well have been piqued at Ghalib’s admonition, but he had also realized that Ghalib’s feel of the circumstances was almost prophetic and his approach was more practical and accurate. He may also have felt that he, being better informed about the English and the outside world, should have himself seen the change that now seemed to be on the anvil. Sir Syed never again wrote a word in praise of Ai’n-e Akbari and gave up taking an active interest in history and archaeology. Instead, he became a social reformer of repute.

A court poet and Ghalib’s good friend had fallen on bad days and could no longer afford expensive clothes. Once, he visited Ghalib in ordinary chintz. Saddened by his plight, Ghalib wanted to give him one of his brocades that he could wear to court. Not wanting to make him feel small or obligated, Ghalib thought of a way out. He praised the chintz so much that his friend said he could have it if he liked. Ghalib promptly grabbed the offer and gave away one of his most expensive dresses in exchange. This was disguised generosity, Ghalib-style.

We are pygmies before Ghalib to even think of writing about him inasmuch as rivers of ink have flowed from the pens of innumerable intellectual commentators, yet none can say with confidence that he or she has come to know the person of Ghalib unless s/he wore, like Ghalib, a bleeding-heart of a humanist. I could do no better than to sample these few pearls and gems from the precious treasury of his lyrics.

Game Hasti ka Asad kis se ho juz marge ilaaj

Shama har rang mein jalti hai sahar hone tak

(Only death can end the pain of the moth playing with the flame. And yet the flame must keep burning in all shades till it is dawn)

Bas ke dushwaar hai har kaam ka asaan hona,

Aadmi ko bhi maessar nahi insaan hona

(We live in an age where everything seems such a task, One cannot even afford to be human these days.)

Hai aadmi bajaye khud ik mahshare khayal

Hum anjuman samajte haie khalwat hi kuon na ho!

(This creature we know as man is one big chaos of desires and thoughts. Even when lonely he is never alone for in his breast lay hidden a tumultuous crowd)

Go haath ko jumbish nahin, aankhon mein to dum hai/rahne do abhi sagaro mina mere aage

(The hands cannot move but donot remove the goblet or the wine for I can dine with my eyes for they are still alive)

I don’t find myself adequately qualified to compare the two stalwarts of Urdu language and literature as is often done by most of the writers on the subject. I somehow feel that nature has its own way of validating our beliefs. While my all childhood prize possessions including Bange Dara got consigned to fire along with my ancestral home in Kashmir set ablaze by the terrorists, my new home in Delhi is thriving with over a dozen Dewans, just in case a friend drops in.

Bhushan Lal Razdan, formerly of the Indian Revenue Service,

retired as Director General of Income Tax (Investigation), Chandigarh.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts, analysis, assumptions and perspective appearing in the article do not reflect the views of GK.