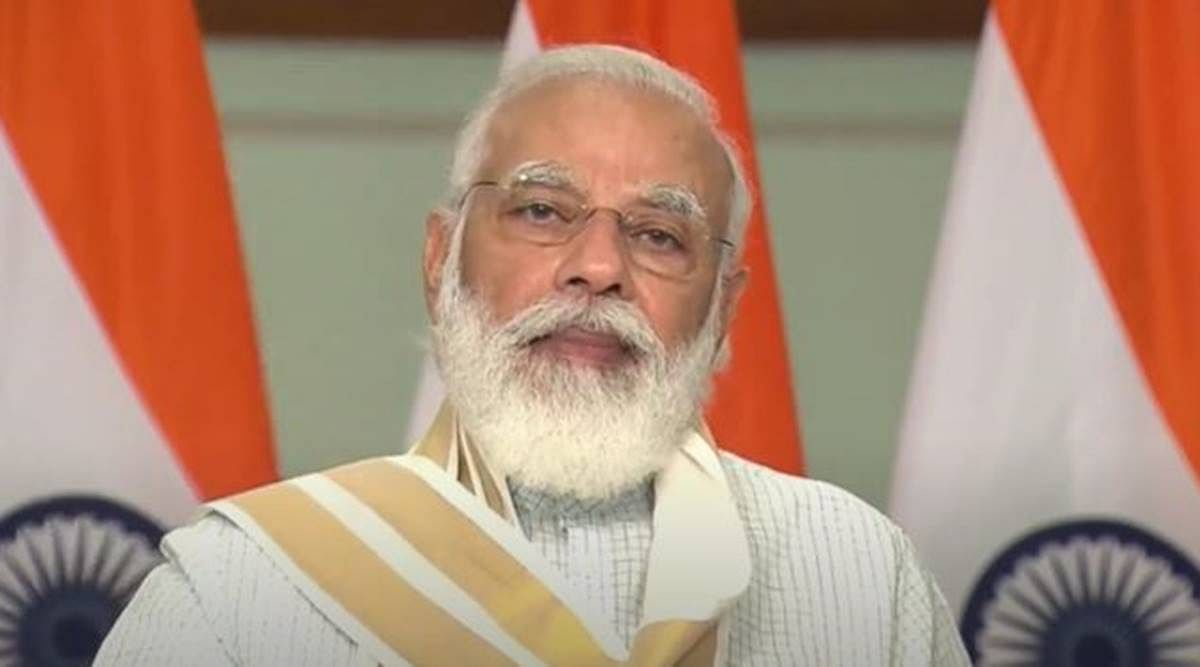

The 16th Pravasi Bharatiya Divas (PBD) Convention was held in virtual mode on January 9. Prime minister Narendra Modi gave the inaugural address to this annual gathering of the Indian diaspora. The Suriname president Chandrika Persad Santokhi who was the chief guest at the event delivered the keynote speech. The valedictory function was graced by president Ram Nath Kovind. Two plenary sessions were convened during the convention. The first focused on the role of the diaspora in Atmanirbhar Bharat while the second centred on Facing Post Covid Challenges.

The fact that the Modi government decided to go ahead with holding this premier event diaspora event—although in virtual mode– despite the ongoing COVID-19 situation only demonstrates the significance that the ruling dispensation attaches to keep links with the diaspora nourished and active. This is also shown by the keen participation of external affairs minister S Jaishankar who was present in not only the inaugural and valedictory sessions but also took part in the atmanirbhar bharat plenary. Indeed, the diaspora connect is an important component of Modi’s foreign policy.

The government’s view on the significance of the diaspora is obviously based on the conviction that it can play a role in promoting the country’s national interest by acting as a bridge and enabler between India and many countries. As the diaspora’s profile has risen in the world with it gaining political, social, economic and professional prominence in a large number of countries, including some advanced states, it can make a contribution to enhancing bilateral ties.

There can be a downside because the diaspora can then seek to also influence domestic developments in India. Non-resident Indian nationals have an obvious right to do so though they cannot exercise their voting rights abroad. However, even though people of Indian descent are entitled to hold “Overseas Citizens of India” cards they are not entitled to vote or take part in political affairs for India does not recognise dual nationality. Hence, how should the Indian government react if this segment of the diaspora either directly or through foreign governments seeks to influence purely domestic issues? This has to be studied in some measure for people of Indian origin can now take part in the nation’s economic life. Hence, do they have a right to intervene in the country’s economic policy and legislation?

This matter came up during the farmer’s protest. Not only did Canadian political leaders of Indian descent, but also that country’s prime minister Justin Trudeau make comments on the farmers’ agitation. Naturally, it was completely inappropriate for Trudeau to respond to what is an internal matter of India. But with the rising political profile of the Indian diaspora in Canada the country’s politicians take an interest in matters which concern their electorate, including that of Indian origin. Traditional diplomacy will have to evolve to handle such situations.

In his inaugural address Modi praised the progress of the diaspora, its commitment to its cultural roots and connect with India. There is no doubt that large sections of the diaspora show an interest in adhering to some aspects of their ancestral traditions which are derived from India. It is necessary to encourage them in this regard while being aware that culture and language keep evolving and the culture of the coming generations of the diaspora will change over time. What should be attempted is to attract them not only to an India which is growing economically and show them opportunities for them in this process but also to put before them an India which remains committed to its constitutional values and inclusiveness.

Modi made three points which deserve special mention. He said that during the period of ‘slavery’—obviously a reference in this context to the period of British colonialism— ‘scholars’ felt that India was ‘divided’ and hence could never gain freedom but the Indian people proved that these predictions were wrong. This is correct for colonial masters always publicised the racist view that Indians were incapable of taking on the responsibility of a sovereign nation.

Modi’s second point was that after independence many felt that a ‘poor and not so literate’ India would break up and was incapable of sustaining democracy. However, these prophets of doom were incorrect. Indeed, right from 1952 when the first election based on universal franchise was held the Indian people showed that there was no co-relation between literacy and the knowledge of self-interest and national interest which led to democratic political choices. This was a lesson with universal applicability as the world de-colonised in the 1950s and the 1960s.

Modi’s third significant point related to the focus on science and technology amidst poverty and illiteracy. It is here that Jawaharlal Nehru showed the path with making investments in the institutions of scientific and technological knowledge. He also paid attention to nuclear and space programmes when many advanced countries wondered about their relevance in an impoverished under-developed country. In short time India showed that advanced scientific and technological skills were the path to true progress. The Modi government has done well to apply the scientific tools of the digital age to governance. Through these applications the fruits of development can reach the poorest Indians. The ultimate test of all developmental programmes is in securing the progress of the most vulnerable.

Ultimately, an India that is rooted in constitutional values and in modern science and technology even while adhering to worthwhile historic traditions will be a sure attraction for the Indian diaspora.