BY SALEEM RASHID SHAH

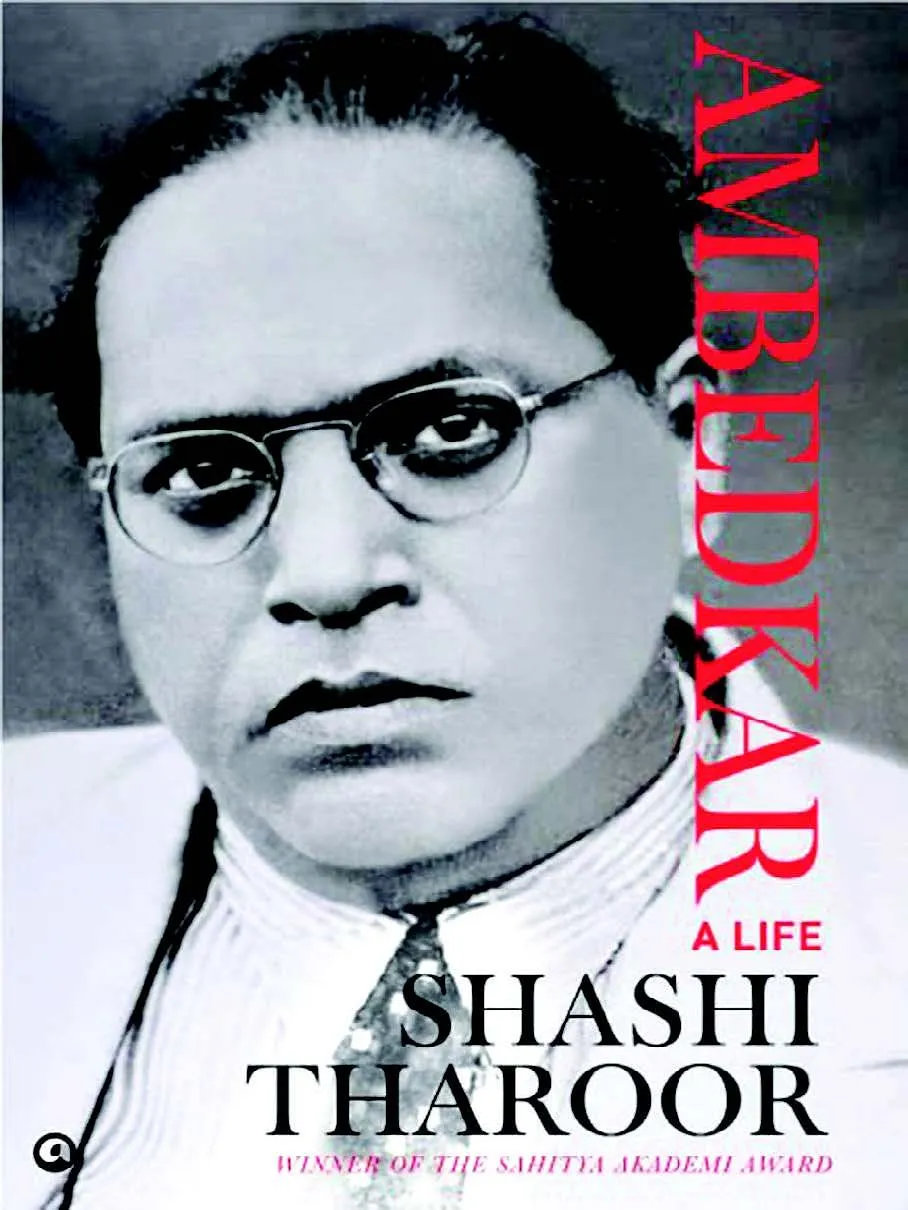

Babasaheb Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, MA, MSc, PhD, DSc, DLitt, Bar-at-Law, has been the subject of many biographies. However, in Ambedkar: A Life, Shashi Tharoor tries to explore different strands of Ambedkar’s life that proved pivotal in transforming the fate of millions around him with the force of his intellect, and the power of his pen.

This book tries to fill the deficiency left by the previous biographies of Ambedkar. In Tharoor’s words, “It is the story of the rise of a man of ideas explained through extensive quotations from his writings and speeches, and not of a man of physical adventure.”

Tharoor starts the biography with an important caveat of being acutely conscious of the fact that somebody down the line will object to this book on the basic ground that he was not a Dalit himself.

He is aware that the analysis of an ‘objective author,’ however well read cannot match the personal insights and experiences of discrimination by the marginalised.

He begins with a pledge of having approached the subject of his biography with respect for the man, admiration for his accomplishments and awareness of the context. Tharoor leaves for the readers to judge whether the result of his efforts is good enough.

The book begins with an invitation that a nine year old boy receives from his father, an untouchable subedar in British Indian army telling him to come over and spend his summer holidays with him in Koregaon.

The prospect of journeying by a train for the first time thrilled the nine year old boy and his two companions, a brother and a cousin. Upon arriving at the railway station no cart owner was ready to transport them to their father’s place.

The sight of three untouchable boys from the Mahar community stranded at a railway station scared off the cart owners for the fear of being polluted. This nine year old boy on whom this incident had a profound influence was called Bhim.

The talent and the capacity for hard work with a fiery dedication to do something with his life was readily visible in Ambedkar but the want of money and his family’s financial depredation put his dreams at a halt.

In those tough times a free thinking Maharaja of Baroda, Sir Sayaji Rao Gaekwad came to his rescue and granted him a scholarship first of Rs 25 a month to complete his college education.

Later a princely sum of 11.50 pounds per month for three years to study in the United States, in exchange for a commitment to serve Baroda state on his return for a ten year period.

His masters thesis on ‘The Commerce in Ancient India’ won him an MA in 1915 in Columbia and later as the contract was over he was called back by the Maharaja to serve in the state as per the commitment. Ambedkar came back and the Maharaja gave him a warm welcome.

He was named as Maharaja’s military secretary but the irony was that he did not find a place to live because of his identity of being an untouchable. He later recounted that ‘My five years of staying in Europe and America had completely wiped out from my mind any consciousness that I was an untouchable, and an untouchable wherever he went to India was a problem to himself and to others.’

Ambedkar, now homeless, spent a night in a public park with his belongings, his books and even his certificates from Columbia strewn around him on the ground. Despite his degrees in Columbia, this was what life in Baroda had reduced him to.

His urge to break free from the shackles of caste system and to pull out his people from this morass got him involved in the politics of the day. The headway was made when as a young professor of Economics in Sydenham College, Ambedkar was invited to testify before the Southborough Committee, which was preparing the Government of India Act 1919.

Later, in 1924, he set up an organisation ‘Bahishkrit Hitakirini Sabha’ with a motto of ‘Educate, Organise and Agitate’ to fight for the rights of the Depressed Classes and to speak on their behalf to the authorities.

He called on this organisation to also fight for swaraj, independence from the British rule but also said that “the political power cannot be the panacea for the ills of the Depressed Classes. Their salvation lied in their social elevation.”

When in 1930 British called on the First Round Table Conference to discuss the political destiny of India, Congress boycotted it but Ambedkar went to raise two important issues.

He talked about the failure of British government to remove the caste system and empower depressed classes whose position had been reduced to worse than that of serfs and slaves.

He also did not spare his hosts and maintained that the untouchables in India are also for replacing the existing government by a government of the people, by the people and for the people.

He stated that, “We must have a government in which men in power know where the obedience will end and the resistance will begin.” It is said that even after the conference ended in shambles, Ambedkar was perhaps the one delegate who emerged from the collapse of the conference with his reputation enhanced.

Tharoor talks of the first meeting between Ambedkar and Gandhi where the latter took some time to notice him and kept conversing with others. Ambedkar wondered whether he was being deliberately insulted.

Ambedkar’s disinclination to acknowledge Gandhi as a ‘Mahatma’ and his insistence on referring to him only as ‘Mr Gandhi’ sprang from a doha by Sant Kabir, ‘Manus Hona Kathin haya tou sadhu kahan se hoya?’–It’s difficult enough to be a man, how will you become a sage? In this first meeting between Ambedkar and Gandhi, Gandhi gave assurances of his support for untouchables but Ambedkar was not satisfied and the meeting was not a success.

After Stanley Baldwin announced the Communal award and decreed that there would be separate electorates for various communities including the depressed classes, Ambedkar welcomed it but Indian National Congress rejected it outright. Gandhi went on a fast unto death until the award was withdrawn.

This set Ambedkar and Gandhi on loggerheads with each other which eventually culminated with the signing of the Poona Pact between the two. Ambedkar relented and hence saved the life of Mahatma.

Some saw this pact as a historic compromise that would guarantee depressed classes representation and some said that Ambedkar had surrendered to Gandhi and sold out the interests of his people.

The personal aspect of Ambedkar’s life is very well dealt with in the book. The role of Ambedkar’s wife Ramabai has been thoroughly explained as a woman who supported his husband in the times of extreme penury.

Ambedkar’s stance on the empowerment of women has been well ahead of his time and his insistence on educating women has been hailed world over. He was clearly against child marriage and stated that ‘each girl who marries should stand up to her husband, claim to be his friend and an equal, and refuse to be his slave.’

Ambedkar, says Tharoor, was undoubtedly an early feminist.

Carving out a place for him in the Constituent Assembly, Ambedkar as the Chairman of the drafting Committee of the Constitution spearheaded the monumental task of giving a start up nation its first constitution. A document which in Ambedkar’s words was ‘workable, flexible and strong enough to hold the country together both in peace time and in wartime.’

Ambedkar, according to Tharoor was a ‘Political Misfit’ who had lost more elections than he had won.

A perceptive commentator in Times of India once described Ambedkar’s political life as ‘a tragedy of a man who thinks that rationality is applicable to politics and argues from premises to conclusions.

But the vast herd of politicians is not rational. They argue backwards. They adjust their premises to support their conclusions.’

In an everlasting war between deep seated socio-political discrimination and individual rights, Ambedkar always upheld the cause of an individual. He turned the Gandhian argument on its head and said that the Draft Constitution has discarded the village and adopted the individual as its unit.

Hailed as India’s James Madison, Ambedkar became the principal author of India’s constitution. Every political party of India today feels obliged to express their admiration for him. In this biography the author shows how Ambedkar entered the rare pantheon of the unchallengeable.

Saleem Rashid Shah is an avid reader of socio-political non-fiction. He is currently pursuing Masters in English Literature from JMI, New Delhi.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author.

The facts, analysis, assumptions and perspective appearing in the article do not reflect the views of GK.