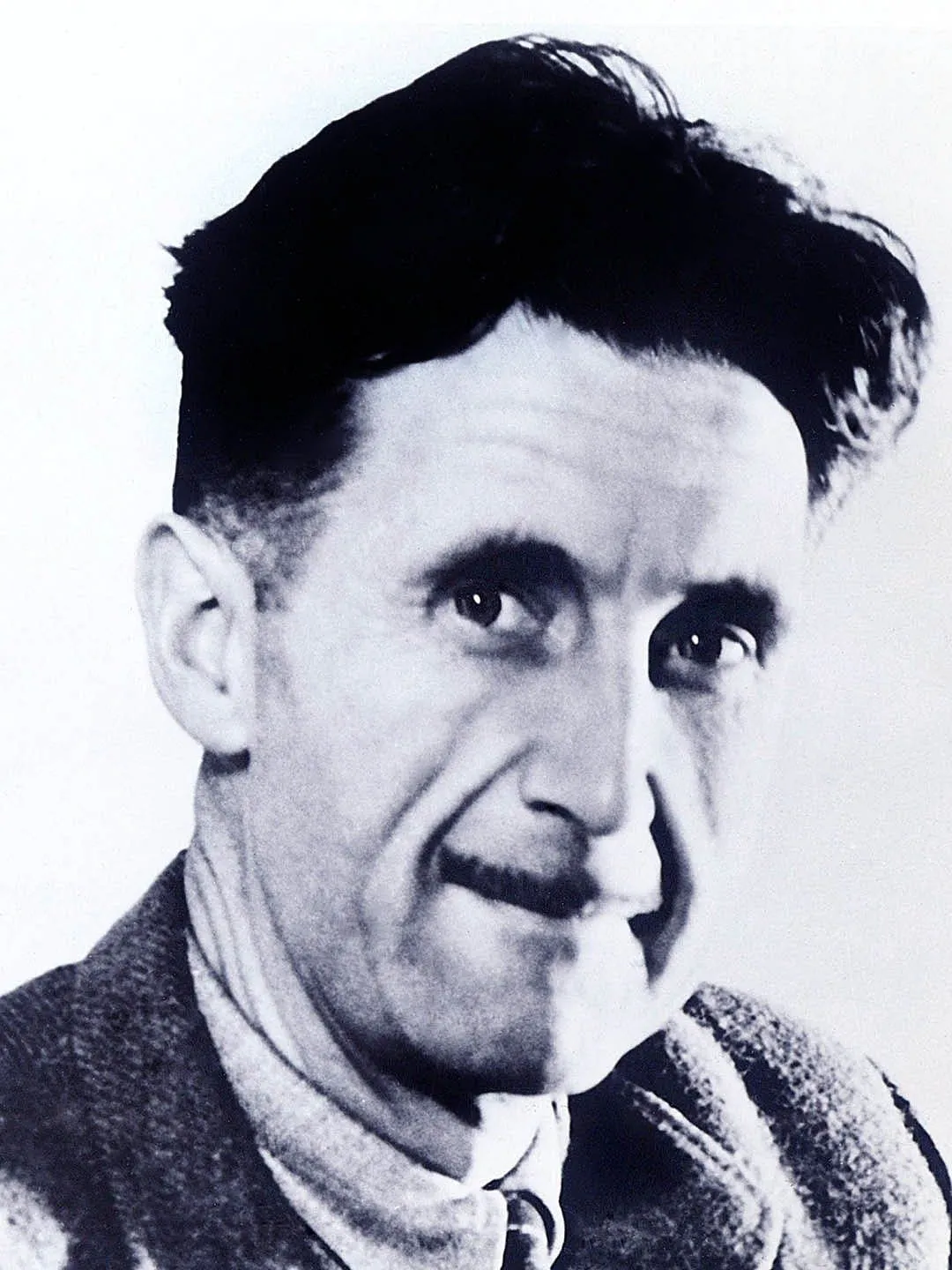

Eric Arthur Blair, famously known by his pen name – George Orwell; lived in a quintessential age of politics – the dawn of Communism, the threat from Fascism, the beginnings of the Cold War and nuclear age, and most of all – the misery of a common man. His life was as politically adventurous as his writings – but, I would have to confine this essay to his insightful and iconoclast writings – which beautifully wed personal with the political – which are straight and honest, as truthful as a mirror and as imaginative as a work of art.

The thought of George Orwell, and subsequently, its expression was shaped by his own life, experiences and involvements – His pen did not exhibit the cold detachment of a sophisticated philosopher – it poured tears and blood – it spoke for the ‘invisible’ – ‘the poor drudges underground, blackened to the eyes, with their throats full of coal dust, driving their shovels forward with arms and belly muscles of steel’, to whom, Orwell remarked, ‘all of us really owe the comparative decency of our lives.’ It was one of the many spurts of poetic candour – in which, with graphic diligence – Orwell presented the brute realities of ‘proletarian’ life. While esteemed journalists and what Orwell referred to as ‘Bourgeoisie – Socialists’ preferred to see, from an arm’s distance – what their class or party demanded; Orwell had a necessary, though somewhat unusual, courage to look at the stark realities of political arena and of daily life.

On one occasion, Orwell points out; while the ‘Stalinists were in the saddle’ and Barcelona felt like a ‘lunatic asylum’, the Dutchess of Atholl, among English visitors, ‘flitted briefly through Spain, from hotel to hotel’ and noted,

‘I was in Valencia, Madrid, and Barcelona … perfect order prevailed in all three towns without any display of force. All the hotels in which I stayed were not only ‘normal’ and ‘decent’, but extremely comfortable, in spite of the shortage of butter and coffee.’

Orwell remarked with satirical derision, ‘It is a peculiarity of English travellers that they do not really believe in the existence of anything outside the smart hotels. I hope they found some butter for the Duchess of Atholl.’

Meanwhile, in the same book – Homage to Catalonia – he leaves no stone unturned to describe in vivid detail how the Communist press misrepresented facts on the ground; to an extent that, ‘…they are so self-contradictory as to be completely worthless.’

He rightly alluded to a personal revelation of war- ‘One of the dreariest effects of this war has been to teach me that the Left-wing press is every bit as spurious and dishonest as that of the Right.’

For someone who wanted to be part of ground reality – who fought on the Republican side; during the Spanish civil war, who understood first-hand the perils of Colonialism in Burma, who lived with tramps and paupers – an elitist detachment from the grotesque realities of conflict and poverty, as well as the condescending world of Communist jargon; were deeply distasteful – Orwell was more interested in what the workers were actually fighting for – ‘decent life’ (a word that he used very often) – which he elaborated in his reminiscences of the Spanish war as,

‘Enough to eat, freedom from the haunting terror of unemployment, the knowledge that your children will get a fair chance, a bath once a day, clean linen reasonably often, a roof that doesn’t leak, and short enough working hours to leave you with a little energy when the day is done.’

This was Orwell’s idea of Socialism – which he expanded and expounded in fair detail – The second part of ‘The Road to the Wigan-Pier’ being devoted solely to the purpose. Socialism, which he defined as – ‘justice and liberty when the nonsense is stripped of it’ – nonsense, which to him meant the unnecessary Marxist phraseology, the almost metaphysical beliefs of some Communists and othering people who naturally fell in the non-privileged section of the populace – was to him the bulwark against Fascism and the hope of mankind. In his ‘Lion and The Unicorn’, he went further, to deliberate on the Socialist polity and its immediate tasks – as he understood it. What Orwell intended, he expressed profusely in ‘Why I Write’ – ‘Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it.’

Though Orwell wrote both fact and fiction, in many of his essays and books – his last works of political satire, in ‘Animal Farm’ and ‘1984’, have since then become the epitome of Orwellian thought – and I believe, rightly so. But, without understanding the background of Orwell, without understanding how his experience as a policeman in Burma gave him his first taste of the slave-master relation – on which he later remarked ‘In order to hate Imperialism you have got to be part of it.’, without understanding his partaking in the Spanish civil war, in which he saw truth being murdered; both by the traditional left and right, without understanding his disgust for poverty and squalor, when abundance was available – one may not be able to frame a proper context to these two works of fiction. One may confine it to Soviet Russia or Communist regimes – which Orwell intended as a general manifestation of tyranny, oppression, and totalitarianism. Most of all, in these two works, he deciphered, like none else, how the master-slave relation is not only about taking control of the political organs of the state, but, a coup on the human soul itself – In 1984, as Winston was told ‘…power is power over human beings. Over the body – but, above all, over the mind.’ With his ingenious descriptions of doublethink, Room101, Newspeak, thoughtcrime and the likes – Orwell unravelled totalitarianism to its guts – How the ‘Big Brother’ was in the process of creating ‘Newspeak’ – which by surgically removing unwanted words like justice and democracy; from the lexicon, and ultimately making people ‘quack like a duck’; intended in making even a divergence of thought, from the official-line – ‘literally impossible’. Elsewhere, in the ‘Animal Farm’ – how the seven commandments had been slowly altered, ‘No animal shall kill another animal, without cause.’, ‘No animal shall drink alcohol, to excess’, and ultimately, ‘All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others’ – personified Orwell’s supreme contribution to political thought – unravelling the nexus between political language and power – an insight that he had fairly tabled in his ‘Politics and the English Language’:

‘Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness…A mass of Latin words falls upon the facts like soft snow, blurring the outline and covering up all the details. The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as if it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish spurting out ink.’

It was this insincerity, this dichotomy of word and deed; that Orwell set to expose. And he did so with extreme success – he attacked left, right and centre – Truth was far greater, to be confined in a party manifesto.

Having borrowed the rhetorical question from Christopher Hitchens – ‘Why Orwell Matters’, I may suggest – Orwell matters, because he combined in himself the rarities of divergent crafts – brave journalism, courageous humanism, poetic diligence, novelistic expression and philosophical insight; all of which collated to make – George Orwell. Above all, his writings; whether political or otherwise – are a deep reflection of human sensitivity – he wrote ‘Some Thoughts on the Common Toad’ with the same passion as ‘How the poor die’ – with an answer to his critics, and a suggestion for us, in the former,

‘I think that by retaining one’s childhood love of such things as trees, fishes, butterflies… one makes a peaceful and decent future a little more probable…’

And, above everything else – living life to its fullest intense, and writing; where fact and fiction seem hardly discernible; but equally fascinating – Orwell accomplished, what he ‘most of all’ intended to – ‘make political writing into an art’.