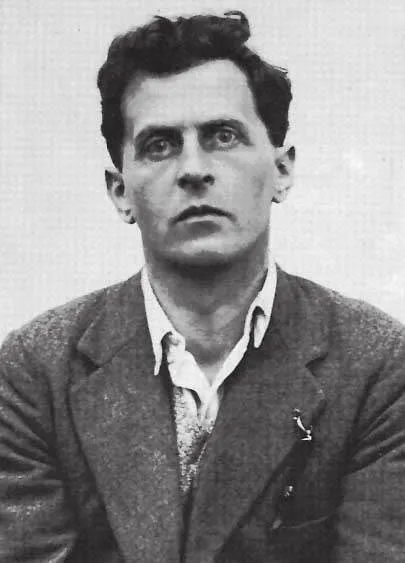

Wittgenstein is one of the most influential philosophers of the twentieth century. He was born on April 26, 1889 in Vienna, Austria, to a wealthy family, well known in scholarly Viennese circles. Wittgenstein had profound influence not only on language but also on the conversations in logic and metaphysics, ethics, and the way how we should live in the world. He published two important books: ‘Tractatus Logico Philosophicus’ (1921) and ‘The Philosophical Investigations’ (posthumously 1953), for which he is best recognised. These were major contributions to twenty century philosophy of logic and language.

The Iconoclastic Quest

With Einstein, Freud and Heidegger (his contemporaries) coming to the age with sort of enfant terribles character of fashioning and redefining the thought of human understanding and universe, Wittgenstein joined the league by starting a new wave of doing philosophy centred around ‘the language’. The status of Wittgenstein in philosophical world is same as that of (his fellow countryman) Kurt Gödel in Mathematics who with the same iconoclastic quest literally shook the permanent nature of ‘reason and proofs’ with his “Incompleteness Theorem”. Wittgenstein came to the scene with the similar nature of ‘zeitgeist’in the world where language formed the quintessence of ‘essence and existence’ of lifeas he would say. Considering a language as the “totality of world in facts not as a thing” where every subset and whole relates to the meanings as Wittgenstein suggests, it is rooted in the human form of life. The basis of any conflict or misunderstanding stems from the communicative failures or undermining the significance of language in our everyday lives. We need language besides other things as we live in ‘public sphere’ this time in Guattarian Post-media epoch where informational convergence happens fast and the semantic fields add on to the conflicts where the world is always infested in many.

Linguistic Turn

Wittgenstein’s Tractatus having less than seventy-five printed pages has been one of the finest masterpiece of the 20th century thought encompassing religion, polity, society etc. It heralded what has consequently been called ‘the Linguistic Turn’ in contemporary philosophical understanding. Wittgenstein wanted to map the world in the realm of associating ‘language and reality’ when we delve into the ‘architecture of life’s grammar’ in his Tractatus. In other words, he endeavoured to ascribe a name (nomen) to every imaginable object in the world (nominatum). Wittgenstein through his trailblazing work in the philosophy of language made us conscious of the fact that there are ‘limits of language’ and taking us further beyond the sphere of language as “whereof one cannot speak thereof one must remain silent’ Wittgenstein’s mythological view of language as social conduct is a manual for anyone for how to communicate effectively within the social formations and interactions. A picture is worth a thousand words, but a well-timed joke can express a world-view. Wittgenstein once remarked that a ‘serious and good philosophical work could be written consisting entirely of jokes’. In the present times we can see the humour shaping the trajectory of socio-political discourse from Hasan Minhaj to Trevor Noah. Wittgenstein was idiosyncratic in his conduct and way of life, yet extremely acute in his philosophical sensitivity. He was highly regarded as moral purist: a man who left all the worldly goods and honors that had been conferred on him in order to lead what he called a “decent” life. He is even said to have helped artists in need financially among them Rilke, Georg Trakl and Adolf Loos. His humility can be seen right through in his personal conduct and even in his intellectual thought. He would define philosophy in the prism of language too by considering it as “Philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of our language.”

The Sacred Meaning

There seems a reflection of pursuit of ‘supreme truth’ in Wittgenstein’s exegetical and mystical essence in his thought when he rivets through the discussion of apocalyptic manifestations and illusion of human progress by summing up as ‘It is by no means how things are’ (Culture and Value, Wittgenstein). Rudolf Carnap recalling his impression of Wittgenstein says “His perceptive outlook was more like of creative artist than those of a scientist….his statement stood before us like a newly created piece of art or a divine revelation……as if insight came to him as through a divine inspiration”. Norman Malcolm’s adds that Wittgenstein’s ‘way of arriving at a philosophical insight is an analogue of a prophet’s way of arriving at a religious insight’. Eli Friedlander equates the division of the Tractatus into seven main sections as being “reminiscent of the seven days in the biblical creation-myth……. ends with the withdrawal and silence of the creator, after all that could be done has been done”.

Philosopher Bertrand Russell while describing Wittgenstein considered him as “the most perfect example I have ever known of genius as traditionally conceived, passionate, profound, intense, and dominating”. To give you a sense of how highly Russell regarded Wittgenstein, Russell at one point considered giving up philosophy, thinking he had nothing more to contribute, following a particularly damning critique by Wittgenstein of one of his manuscripts. In 1929, Maynard Keynes in a letter to his wife, famously announced Wittgenstein’s return to Cambridge by this exhortation “Well, God has arrived. I met him on the 5:15 train.” As he had been previously at Cambridge before World War I and acquiring his godlike status through the publication of his first and only book, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, which became widely recognised as a work of genius by philosophers in both Cambridge and in Viennese intellectual circles. Wittgenstein himself was at first convinced that it had definitive solutions to all the problems of philosophical thought, and consequently gave up philosophy in favour of school teaching. With his return to Cambridge he started again to think about philosophical problems, having become convinced that his book did not, in fact, solve them once and for all.

Limits of Language an Free Speech

In the debate of ‘cancel culture’ mainstreamed lately by the insidious ‘Harper’s Letter’ make Wittgenstein’s famed line ‘limits of language’ more relevant than ever when the lines of ‘free speech’ are getting blurred as what should be ‘cancelled’ and ‘what should be retained’. Bound by ideological and political considerations the concept of ‘free speech’ has been put under scanner again as the ‘expressions’ both literal and non-literal are being appropriated by the conservatives on the one side and ‘liberals’ on the other. New York Times ran an opinion by Philosopher Agnes Callard titled ‘Should We Cancel Aristotle’ which subsumes in that ‘appropriation’ culture and sometimes thinkers getting traduced to the governing ‘ideas’ respectively. Pankaj Mishra and Viet Thanh Nguyen had a dialogue on this in Guardian in the backdrop of the ‘letter’ which further vindicates the location of ‘representations’ and linguistic relativism of Wittgenstein ruling our contemporary political environment.

Tailpiece

In the last moments of his life, he was happy to have the end to his conflicting yet wondrous odyssey to the quest for ‘meaning of everything and being’ as he dwelled in the frontiers of silence and to believe Paul Engelmann one of his close friends, he was always lost breaking through time-space continuum with his ‘contemplative silences’. Mostly misunderstood Wittgenstein would always be remembered as the ‘logical seer’ who tried to understand everything that came his way until he was conquered by his own “language game”. His intellectual and imaginative genius always was his metaphoricalendeavour and aim to show the philosophical fly the way out of the fly bottle.