Kashmir, the most peaceful, culturally cohesive, and socially harmonious region in the world, has undergone the worst sort of violence immediately with the end of cold war, from the last decade of previous century. The suffering unleashed by the violence has touched all Hindus, Muslim’s, Sikhs, and the variety of tribal communities. Writers, both within the region and outside constructed different reasons for this but in this review, I don’t think there is any need to repeat the effort.

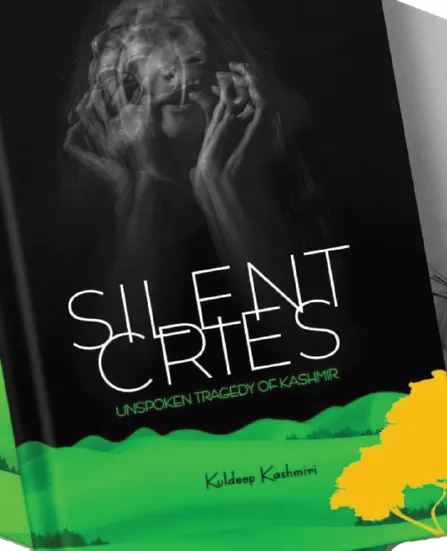

Silent Cries, a fascinating book by Kuldeep Pandita (Kashmiri) is his own voice as a contemporary source to us today. The book – though brief – deeply cares about the topic because the author does situate the wide-ranging problems through stimulating conversation and perspective. While the author productively provokes the Kashmiris to think about important dilemmas confronting people and polity today, but he engages in totalization of scenario and brilliantly shapes the most horrifying incidents in more humane approach for future generations to ponder over.

The book is organized into eight aspects, first three deal with the pre 1990 situation and the other five are devoted to exodus and what followed thereafter. The author has shed light on the socio-religious ramifications and more importantly provided the clues for the way forward. It brings forth the assumption that there is much more to thinking than argument and draws from contemporary perceptions that are rooted in empirical base. The author has argued with a flash of brilliance that Kashmiri pandits’ problem is one in which reflection and judgement are purely culturally constructed and materially determined. Despite immense suffering that the community has undergone including the author himself, Kuldeep Pandita Kashmiri conceives of harmony, coexistence as an important ingredient to ethical political imagination.

“It serves as a stark reminder of importance for fostering society that upholds the principles of peace, harmony and coexistence where such violence and persecution have no place.” (page 32) It shows clearly that the author is very much committed to the kind of civil order and government under which not only Pandits, but all Kashmiris can live peacefully and flourish.

The book stands out in its potential as an important source of reference for future researchers for simplification of excessively complex theoretical positions that scholars and policy makers have taken —these are often seen as arcane by literate Kashmiri public. Kuldeep Pandita Kashmiri’s over all argument is compelling. His ability to incorporate multiple strands of problem, reasons for violence, characterization of suffering and his aspiration to move forward despite all these issues are more apt to be deemed legitimate by all Kashmiris in their dynamic, all constructive relationships irrespective of varied identities. The book is an important contribution and insightful exploration of the way the Kashmiri pandit choices were shaped both for better and worse that are so fundamental to their conceptions of who they are today.

It is an integral part of substantial body of literature for understanding Kashmir problem from comparative perspective. The author’s approach embodies analytic history that is concerned with discovering and describing major trends across seemingly dissimilar events of Kashmir crisis and the author is successful in showing that seemingly unrelated events follow a common pattern. He brilliantly illustrates that behind an apparently chaotic collection of events there is in fact a hidden order Kuldeep Pandia Kashmiri’s range in this book is striking.

His conceptual clarity, and originality is engaging and innovative and of considerable value. What I view the strength of this book and why I so thoroughly enjoyed reading it, is the number of intriguing questions that Kuldeep Pandita Kashmiri has raised, it is empirical contribution and a thoughtful case study to understand the multiple dimensions and forces involving the impact of Kashmir crisis on Kashmiri Pandits both individually and as a community. I congratulate the author for such an excellent work that provides a firm foundation on which future scholars can build.

Besides, this is devoted to important theme that deserves wider audience.

Professor Rattan Lal Hangloo is honorary Vice-Chancellor of Nobel International University Toronto Canada. He is former Vice-Chancelor of Kalyani University West Bengal &Allahabad University. He is originally from village Hangalgund, Kokernag, Kashmir