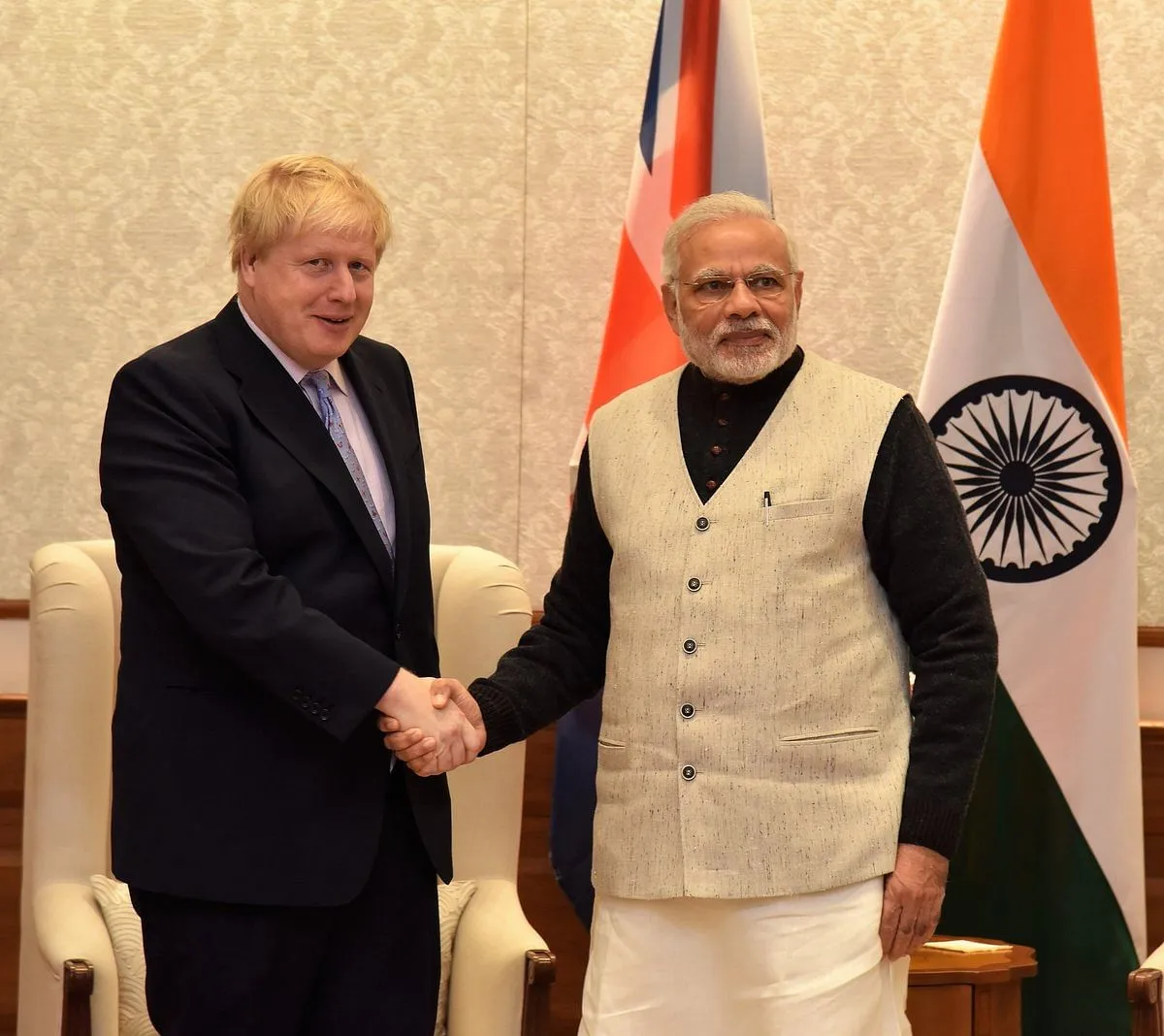

Boris Johnson came on his first visit to India as Britain’s Prime Minister on April 21-22. He was to come earlier as chief guest for Republic Day 2021 but that trip could not take place because of the covid-19 pandemic. He now arrived at a time of great international tension because of the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine.

That issue and the negatives that are emanating from it for international food and energy security no doubt figured high in his interaction with Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In addition regional issues such as Afghanistan also attracted the leader’s attention.

But these did not eclipse Johnson’s emphasis on making the India relationship economically and commercially advantageous to Britain at a time when it is finding its role in the post Brexit era.

The Johnson visit provides a good opportunity to reflect on India’s connection with Britain which began in the early decades of the 17th century with the activities of the East India Company. The Company was founded in the year 1600 and its first ship landed in Surat in 1608. The Company’s objective was trade with India.

At that time Portugal had an outpost in Goa, established in the early decades of the 16th century. Its presence for commerce was more important.

As long as Mughals remained powerful the Company remained an insignificant player on the Indian scene even though it began to maintain forces to guard its trading posts and also intervene in local political affairs.

With the waning of Mughal power the Company began to expand its influence especially around its trading posts—Calcutta, Bombay and Madras, as all three were called till their names changed. In 1757, as every school going child in India knows, the Company defeated the Nawab of Bengal at the battle of Plassey.

It was not a major military operation but its political consequences were historic for India. At the battle of Buxar in 1764 the Company defeated the Mughal armies and thereafter acquired the Diwani of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa the next year from the Mughal Emperor. That gave it the privilege of collecting land revenues. It was no longer only a trading company but became an instrument of British territorial expansion in India.

Gradually, in the next nine decades since the victory at Buxar the Company became the foremost power in India. It vanquished the Mughals, the Marathas, the Sikhs, among others. It either ruled directly or exercised full control over the Indian princes who were at its mercy.

Yet the spark of freedom had not gone from Indian hearts and a great war of independence was waged in 1857. It could not succeed because India was disunited and the Company was scientifically and technologically superior.

While the Company succeeded in 1857 the administration of India was taken over directly by the British Crown in 1858 and for the next nine decades India became a direct British colony.

The British have sought to project their colonialism in India—and elsewhere—as a burden that they undertook to bring the fruits of modernity to peoples steeped in dark superstition. Nothing can be further from the truth.

The colonial enterprise had only one aim: to benefit Britain economically, commercially and strategically. These objectives were fulfilled ruthlessly and with great violence.

The colonial system was completely extractive. The Indian response to colonialism was not on Britain’s account but because of the innate civilisational strengths of the Indian people which helped them launch a comprehensive renaissance that flowering in myriad ways and under great leaders led to freedom in 1947.

The loss of India was the death knell of the British empire. In less than two and half decades thereafter the British empire went into the dust bin of history. After the second world war America became the world’s pre-eminent power and Britain became a small appendage to it.

Yet in large sections of British opinion the memories of empire did not fade away. Often Britain took a patronising approach to the old colonies including India. On its part India’s post-independence leadership while charting an independent path in the country’s development model and in foreign policy bore no rancour towards Britain because they distinguished the British people from colonialism.

All this cannot obscure the malignant role played by sections of the die-hard sections of the British establishment in the years leading to 1947. More and more evidence is emerging from historical records on this subject.

Today India and Britain are committed to define a forward-looking relationship outside the shadows of the past. This is possible because Britain has attempted to adapt to changing times.

This is, in part, increasingly reflected in the presence of large communities of its erstwhile colonies in it; their members are active participants in British public life. People of Indian origin too are successful members of these communities. They form a bridge between India and Britain.

The future of the bilateral India-Britain relationship lies in mutually advantageous trade, investments, scientific and technological cooperation and a willingness on Britain’s part to appreciate Indian security and strategic concerns.

This has not been so in the past because of both Britain’s domestic politics and its desire to have a balanced foreign policy in this region. What Britain really wants now is to focus on economic and commercial sectors and to sell armaments.

That is fine as long as Indian interests are comprehensively taken into account, including through the extradition of those Indian accused of financial fraud who have taken refuge in Britain.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author.

The facts, analysis, assumptions and perspective appearing in the article do not reflect the views of GK.